A book may begin on page one, but the real story starts when a key moment sets the plot in motion. This week, Polly Watt from Fictionary shares how to craft an inciting incident that will hook your readers.

What is an Inciting Incident?

At its most basic, an inciting incident is the event that incites your story.

It’s what triggers all the action, and subsequent reaction, comprising the body of your novel.

At Fictionary, we give the following definition: The inciting incident is the moment your protagonist’s world changes in a dramatic way, giving them a goal or motive they simply can’t ignore.

The inciting incident introduces your protagonist’s story goal – the thing they will work towards as the story develops, and which they’ll either succeed or fail in obtaining at the story’s climax.

It’s this interlacing of story goal, inciting incident and climax which gives overall cohesion and structure to your narrative. Without this, you may find that you don’t have a story, but rather a chain of events – which aren’t linking together quite as they should.

It’s hard to understand what an inciting incident is, and how it should function within story structure, without a basic knowledge of the Story Arc.

Let’s examine this first, before taking a deep dive into how we craft irresistible inciting incidents.

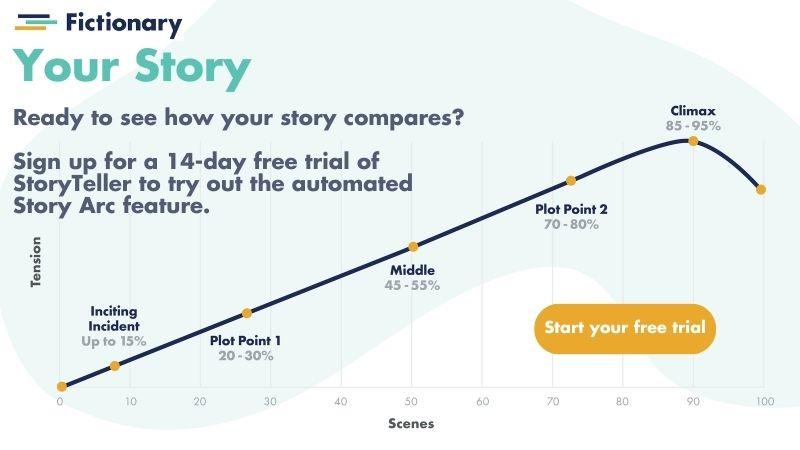

What is the Story Arc?

The Story Arc is a way of visualizing story structure, using concepts that have been in play since ancient times. Stories are divided into three acts: set-up, confrontation, and resolution.

The Story Arc looks at where key plot points happen along the narrative, and how your story’s narrative compares to the ‘ideal’ story development.

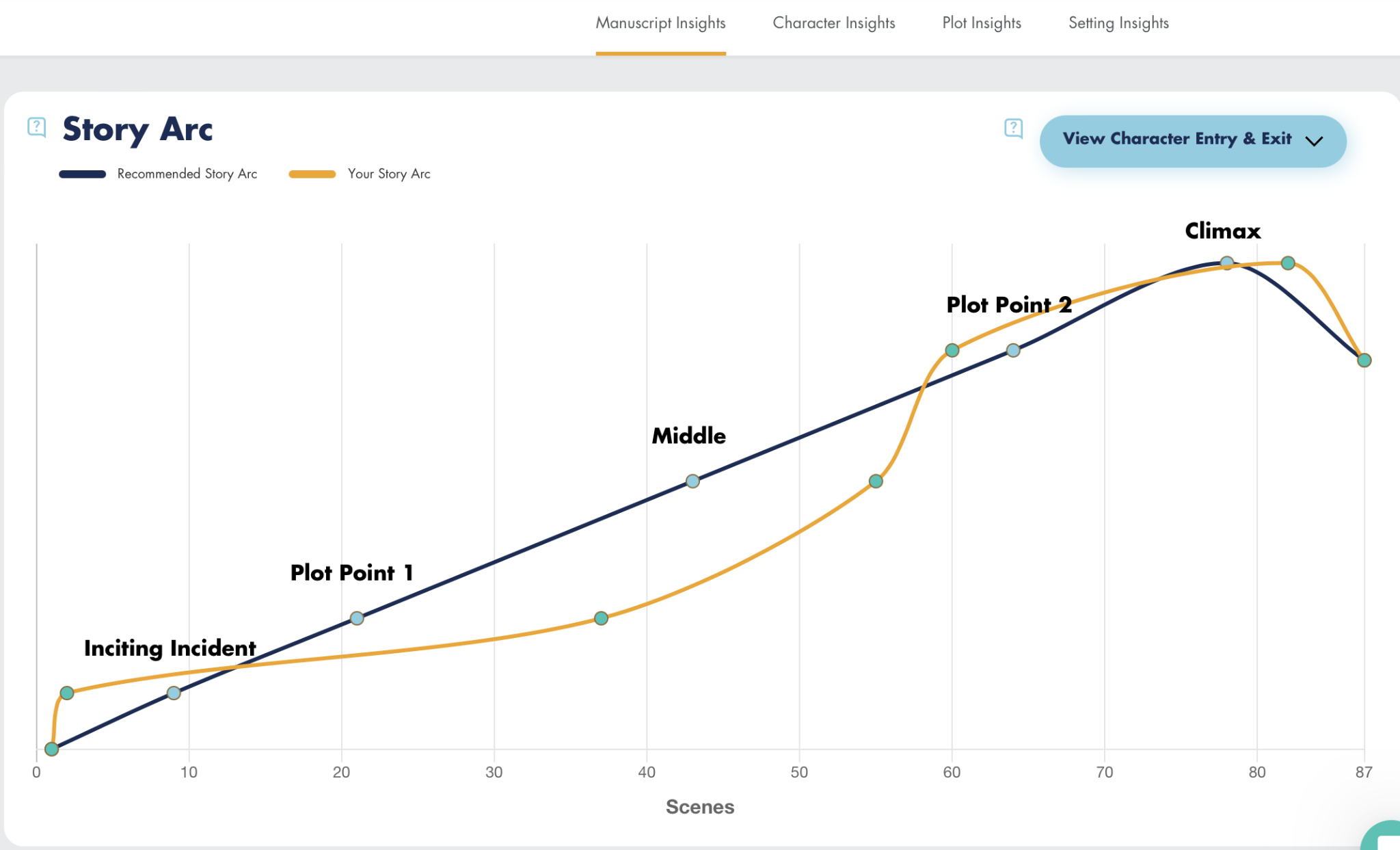

Here’s a picture of how we show the Story Arc using Fictionary StoryTeller software, showing the ideal story arc against that of an example manuscript:

In order to understand the role of the inciting incident, you need to first visualize it in relation to all the other key plot points on the Story Arc.

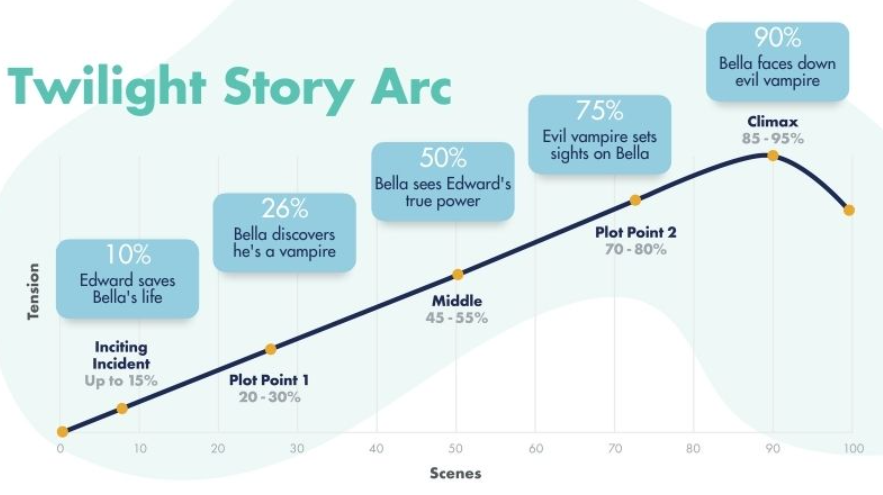

Here’s the Story Arc for Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight:

As the image above shows, the Story Arc maps the following key plot points on the narrative progression:

Inciting Incident:

This needs to come before the 15 percent mark, and it’s when our protagonist’s world changes in a dramatic way, giving them a goal or a motive they simply can’t ignore.

In this case, at the 10 percent mark of Twilight, Edward saves Bella’s life, and she can no longer ignore her fascination with him.

Plot Point 1:

Plot Point One should be between the 20 and 30 percent mark in the story, with 25 percent being the ideal. Plot Point One is the point of no return. The protagonist can’t back out of the central conflict; their desire to engage with it overrules all else. This marks the end of Act One.

In Twilight, Bella discovers Edward is a vampire, and there’s no turning back to her past ignorance now.

Story Middle:

In the middle of your story, the protagonist moves from reactionary to proactive in terms of how they approach their overall story goal. The Middle of your novel occurs between 45-55 percent of the story, ideally at 50 percent.

In Twilight, Bella sees the full extent of Edward’s power as a vampire, yet commits to him anyway.

Plot Point 2:

It’s the end of Act II and the outlook should be grim. Plot Point Two comes at the 70-80 percent mark—ideally at 75 percent—and should be a low point for the protagonist.

In Twilight, an evil vampire sets his sights on Bella, putting her life at risk.

Climax:

The climax comes at the 85-95 percent mark of the story, ideally at 90 percent. The story should build up to the climax with rising action, and now the climactic scene (or scenes) should have the highest level of conflict, the greatest tension, or the most devastating emotional upheaval. At this point in the story, the protagonist should fail or succeed in their overall story goal.

In Twilight, Bella faces down the evil vampire herself, refusing to call Edward to her aid, thus doing everything in her power to protect Edward. It’s a reversal of what happened in the inciting incident.

The Importance of Linking the Inciting Incident with the Climax

As the above example shows, often the strongest, most successful stories feature a satisfying ‘mirror image’ between the climax and the inciting incident.

In Twilight, the inciting incident and the climax work as a perfect reflection of each other, with the former coming at 10 percent into the story, and the latter beginning at the narrative’s last 10 percent. In the inciting incident, Edwards rescues Bella; in the climax, Bella does everything she can do to protect Edward by refusing to call on him to rescue her. He arrives anyway, and thus we see the inciting incident play out in a similar, but different, way at the climax.

It’s this difference between the two moments that illustrates the story’s central theme. Bella is no longer willing to be the damsel in distress calling on her boyfriend to save her; Edward must realize the only way he can ensure her safety in the future is to give her equal strength to his own. Thus, we see Bella’s learning journey from the entire story encapsulated within this difference between these two scenes. She’s learned she can’t protect those she loves without strength – both physical and psychological – and this learning plays out in the trilogy’s next two novels.

As a storyteller, it’s important to remember the power this ‘mirroring’ can carry within story structure.

The story goal is introduced at the inciting incident and answered at the climax: the difference between the initial question and the final answer is how the reader subliminally imbibes the story’s key messages.

This mirroring is one way that you, as a writer, can show rather than tell the reader about your protagonist’s learning journey over the course of the narrative.

Examples of Inciting Incidents That Successfully Hooked Readers

Warning: Spoiler alerts!

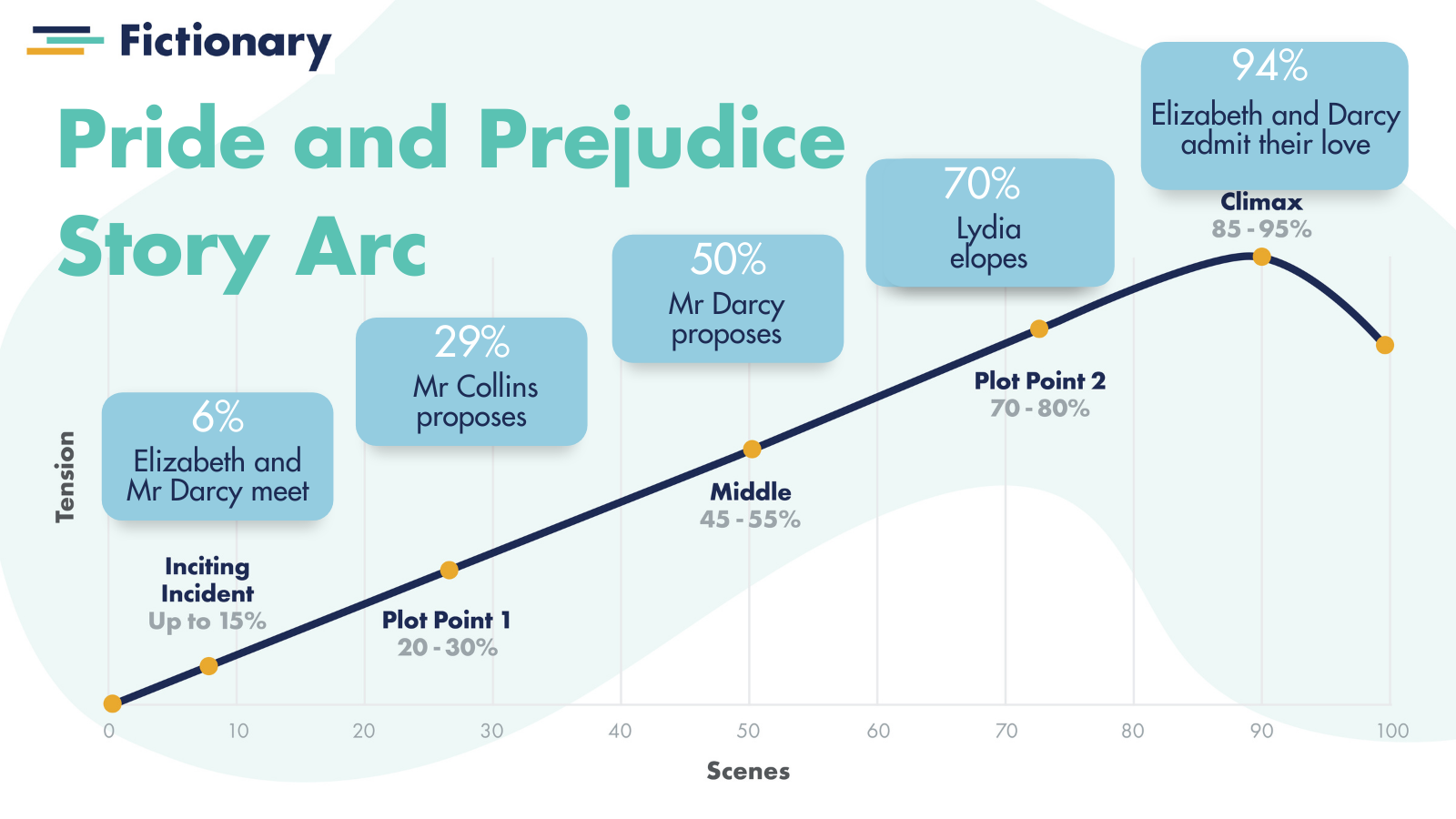

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen:

Let’s examine how Austen’s inciting incident is irresistible to readers.

We’ll analyze this by looking at how the inciting incident works within the context of the story’s set-up at the first 10-15 percent, and how it interacts with the story’s climax at the 90 percent mark.

Firstly, Pride and Prejudice is a romance, so the inciting incident should target the genre’s ideal readers. These readers want to see two deserving characters overcome the odds to find happiness together.

At the novel’s 6 percent mark, Elizabeth and Darcy meet; Elizabeth overhears Darcy describing her in disparaging terms as he rejects the suggestion of dancing with her. This is arguably the novel’s inciting incident, since all of the story’s following action evolves from this one moment.

This scene is mirrored exactly at the 94 percent mark, when Darcy and Elizabeth meet and reveal to each other their true feelings of love.

Prior to Darcy and Elizabeth’s first meeting, Elizabeth’s mother has made the family’s story goal clear: the girls need to get married. Ideally, their mother thinks, to a rich man. Therefore, at Darcy and Elizabeth’s first meeting, we can see how Darcy’s rejection of Elizabeth makes her story goal seem that much harder to obtain.

When an inciting incident occurs prior to the 10-15 percent mark, it can still be helpful to examine what scene does take place at this mark, for greater insight into how the narrative structure functions.

At the 10 percent mark of Pride and Prejudice, Darcy grows aware of his attraction to Elizabeth, commenting on her ‘fine eyes’ to his friends. This means by the 10 percent mark, the reader knows, either on a conscious or unconscious level, that the story arc is likely to answer the question of will Elizabeth and Darcy marry? And how will it happen?

This scene is mirrored in the climax at the 90 percent mark, when Darcy’s aunt, Lady Catherine, visits Elizabeth to warn her to stay away from Darcy, reminding us of the external obstacles in the way of the couple’s potential happy ending.

In between the 6 and 10 percent marks, Austen gives the reader the extra information they’ll need to be fully hooked by the time they’ve reached the 10 percent mark.

For example, in this part of the narrative, Elizabeth clarifies her own version of her story goal, taking it a step beyond that which her mother has for her: she wants to marry for love, not financial convenience.

Elizabeth also tells us laughingly of her own inner failing—pride—which she uses to protect herself against Darcy’s rejection of her.

This means that by the time Darcy admits to his friends that he’s attracted to Elizabeth at the 10 percent mark, Austen has fully developed the story’s potential for external conflict and internal character growth—and it’s these two areas that really hook the reader in.

We’ve enough information to comprehend that Darcy and Elizabeth will never marry unless a) she learns to overcome her hurt pride, and b) she believes they are a true love match, and c) he learns to overcome his prejudice against her.

These are a lot of strong questions, asked by the story’s 10 percent mark, which hook romance readers into turning the pages, all the way until the climax provides us with answers.

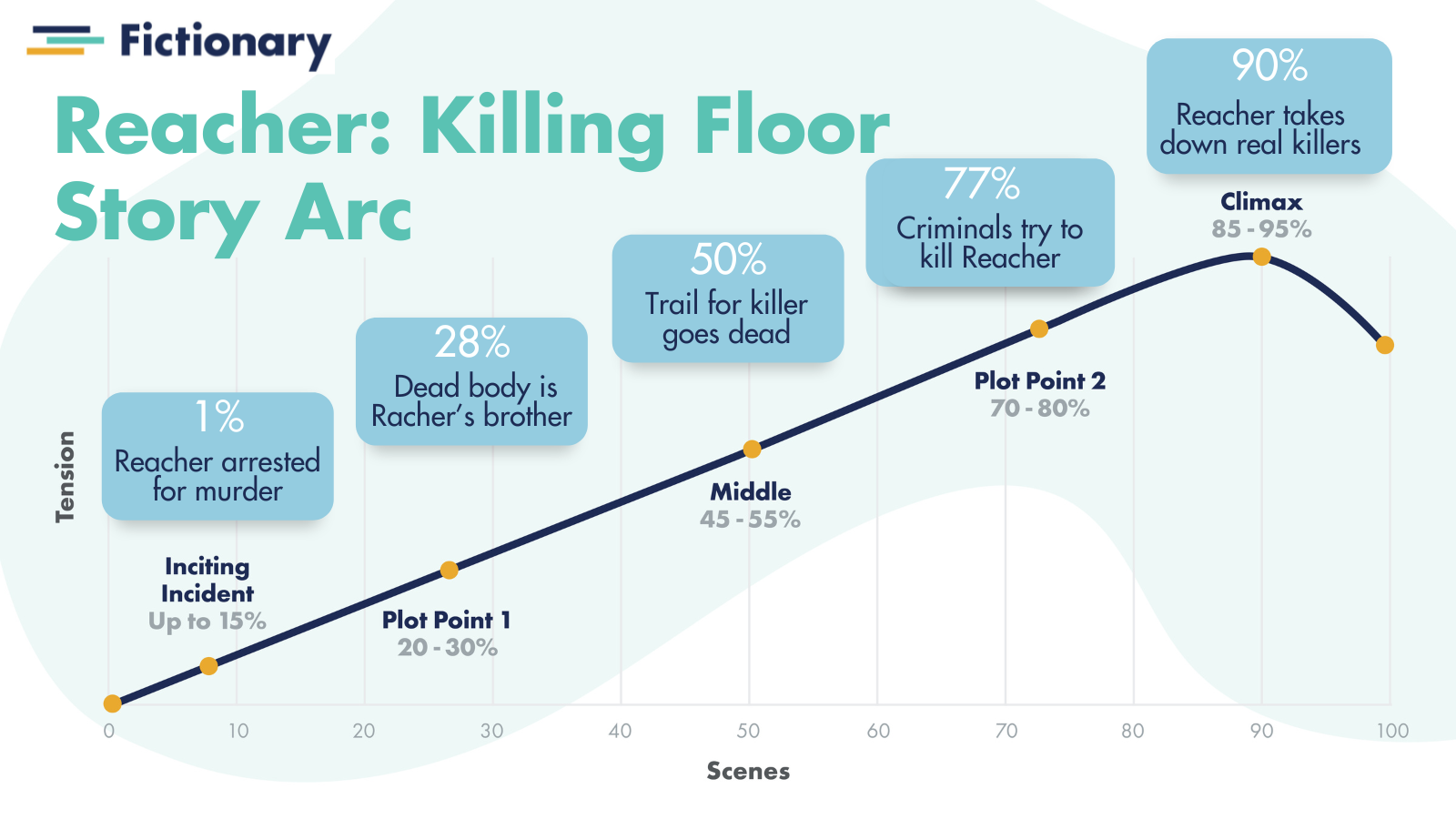

Reacher: Killing Floor by Lee Child

This novel’s a thriller: the inciting incident should entice readers through high, life-and-death stakes and promises of nail-biting action.

Here, the inciting incident happens on the first page: Jack Reacher, an ex-military cop, is falsely arrested for murder.

This event sets him off on his story goal of catching the real killer.

The high stakes alone make this inciting incident irresistible to readers. We know Reacher’s innocent; we know Georgia has the death penalty. There isn’t much more information Child needs to get across to us so that we’ll care about the story’s outcome.

But once again, to understand how brilliantly crafted this story actually is, it helps to examine the inciting incident in conjunction with the scenes placed at the novel’s 10 and 90 percent marks.

At 10 percent, the police contact the man who, according to the evidence, really should be their prime suspect: a Mr. Hubble. But Hubble’s a settled, respectable guy; the police doubt he committed the crime. Reacher, the drifter, seems to them a far likelier suspect.

At the narrative’s 90 percent mark – the story’s climax and mirror image of the 10 percent mark – Reacher himself finally succeeds in tracking down the missing Hubble. This time, Hubble’s fled for his life from the real killer, but he’s the man with the key to unlock the murder mystery. Hubble’s involvement in the crime came, we learn, from his desperate desire to retain the façade of his settled, respectable life after losing his job.

As in Twilight, this mirror imaging of the first and final 10 percent illuminates the inner growth arc of the character. The key difference is that in Twilight, the mirroring shows us Bella’s growth. Whereas, in Reacher: The Killing Floor, the mirroring shows us the justification for Reacher’s lack of growth.

Reacher’s introduced to us as a loner: a man with nowhere to go, who jumped off the bus at a stop in Georgia because it reminded him of a story about a guitarist whose music he liked. By jumping off at this exact moment, he got unlucky, placing himself right at the scene of a crime he didn’t see happen.

As the inciting incident unfolds in the first chapter, we can’t miss one of the key questions about Reacher: will this man ever choose to settle down? Will he be able to, if he wants to? Right from the get-go, we see an urgent external need—to prove himself innocent—alongside the potential for internal growth—can he find a home? The combination of external and internal goals works as another strong hook.

As the narrative plays out, we see our protagonist Reacher crave connection and stability, yet he still rejects them in the end. And through the author’s careful use of story structure, we can’t help but understand why. After all, it was Hubble’s need for external respectability, his desperation to keep his stable home and marriage, that became his downfall.

Reacher, on the other hand, we understand, is above all that. He’s someone who’ll drift from story to story, taking his keen sense of independence and justice wherever he goes.

And his potential for future stories seems endless.

Child’s inciting incident, along with the narrative’s first 10 percent, and the use of ‘mirroring’ within his story’s structure, doesn’t just introduce readers to one story. It introduces them to an entire series of stories.

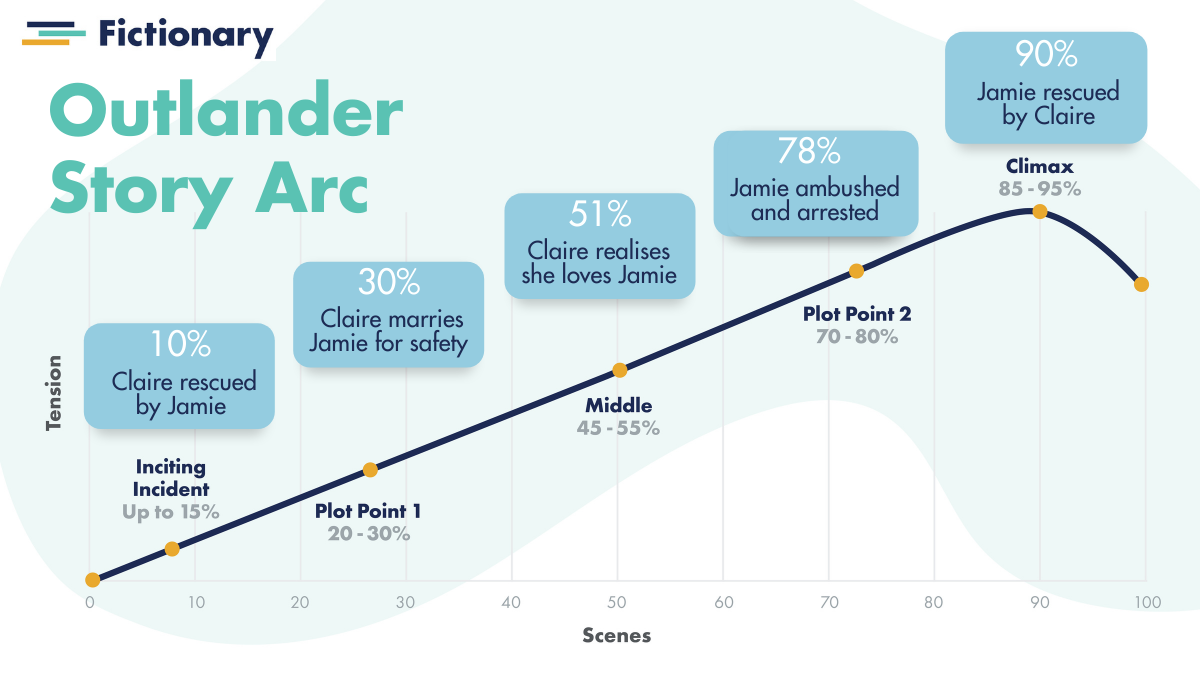

Outlander by Diana Gabaldon

As a speculative historical action/ romance crossover, to be irresistible to her target readers, Gabaldon’s inciting incident must include both high stakes of life-and-death action, and the will they/ won’t they get together question of romance.

This inciting incident seems to occur at the 7 percent mark, when protagonist Claire, on a trip to a standing stone circle in the Scottish Highlands, accidentally falls through time and ends up in the 18th Century. This sets her off on her perceived story goal of getting back to her life and her husband in the 20th Century.

At the story’s 10 percent mark, however, Claire becomes acquainted with the Highland rebel Jamie, the man with whom she will end up falling in love. Her true story goal, that of finding and keeping real love, is introduced here, at the 10-12 percent mark.

These two scenes, at the 7 and 10 percent marks, work together beautifully to craft an utterly irresistible inciting incident for Gabaldon’s target readers.

By the time that Claire falls into the past at 7 percent, we’ve seen that she barely knows her 20th-century husband Frank, since the two have been separated by the Second World War. There’s a hint Frank may have been unfaithful to her over that time. Claire and Frank are desperately trying to get to reconnect as the story opens.

But their attempts are strained. They’re struggling to conceive, and Frank isn’t happy with the prospect of adopting—he doesn’t want to share Claire with anyone, unless it’s their own biological child, which gives us a hint that this relationship isn’t as healthy and strong as Claire wishes it were.

So, when Claire falls through time and meets Jamie, we understand why she’s the right protagonist for this story. By leaving her own world, she’s given the chance to learn to exist as an independent woman, and then to form a love that’s strong enough to survive battles and wars without fraying. And to have the choice to decide whether Frank is her Mr. Right, or whether it’s only a reluctance to break social expectations, which has kept her in her 20th Century marriage.

By the time Claire gets to know Jamie at the story’s 10 percent, we want to see both whether she can survive living in the past (high action stakes) and whether Jamie will turn out to be the man for her (the romance question).

The 10 percent mark and the 90 percent mark of Outlander also mirror each other beautifully.

At 10 percent, Claire has a frightening encounter with Captain Randall and is rescued by Jamie and his gang (who were Randall’s original targets.) Claire leaves with Jamie’s group, and her wartime nursing skills are put to the test as she patches up a physically wounded Jamie.

At the story’s 90 percent, Claire rescues Jamie from imprisonment by Captain Randall—Jamie having sacrificed himself to protect Claire. Claire spends the final 10 percent of the narrative helping Jamie recover psychologically from his trauma. She succeeds, and is thus able to help her 18th Century husband Jamie recover from trauma and reconnect with her—in the way that she wasn’t able to help her 20th Century husband, Frank. This shows us that Jamie truly is the man for her.

Conclusion: What can we take away from these three examples?

These examples show that irresistible inciting incidents generally display certain features:

- The inciting incident must introduce the story goal, making your target readers ask the right questions for your story’s genre—questions that will keep them turning pages.

- By the first 10-15 percent of the narrative you want your readers to understand the story’s central conflict and stakes. Conflict and stakes must be appropriate for your genre.

- To help your readers care about your protagonist, give your protagonist depth: an internal flaw they must overcome, an internal desire or craving for something they need. Ensure that you’ve shown this within the story’s first 10-15 percent so that the reader understands why this is the right inciting incident for this protagonist; the right protagonist for this story. Ensure that by the story’s 90 percent, through the mirroring of inciting incident and climax, the reader understands how and why the protagonist has overcome—or failed to overcome—this internal flaw.

If this all sounds rather overwhelming, you might find it helpful to check out Fictionary StoryTeller’s free two-week trial. With StoryTeller, you can visualize your own manuscript’s Story Arc, examining how your inciting incident and climax work to mirror each other, and you can explore ways of moving scenes around to ensure they’re in the best possible place. Or, come along to our free community, where writers and editors discuss story structure in depth.

As a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editor, Polly Watt will carry out a detailed developmental edit of your manuscript, providing objective, actionable feedback. She seeks to inspire you with fresh perspective and ideas, so that you can make your story shine to its fullest potential. You can learn more about Polly and other StoryCoach Certified Editors at Fictionary at https://fictionary.co/editors/